I am beginning a new painting of von Klenze’s work, this time taking elements of just one building, the Befreiungshalle or Liberation Hall in Kelheim, overlooking the Danube. It celebrates the liberation of Bavaria from Napoleonic rule.

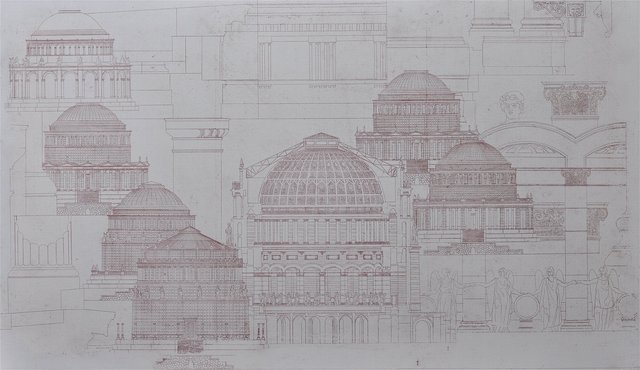

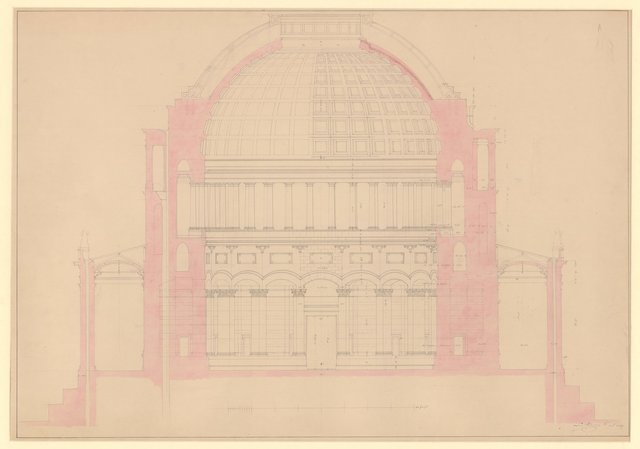

It is a rich subject as it went through numerous changes, having been inherited as a project from Friedrich von Gartner on his death. Following those changes in the painting promises to be interesting, and I have had the luck to stumble on a collection of von Klenze’s working drawings for this building in the Bavarian State Library, which they very kindly allowed me to download and use in constructing the painting. I also came across a technical paper on the renovation of the roof which will allow me to reconstruct the structural ironwork in section. This structure is very interesting being constructed of iron angles and rods into an early version of a lightweight truss, almost a space-frame. The drawings and photos of the restoration work also show small roller-bearings that the frame sits on, this in 1847, some 40 years before the Gallerie des Machines in Paris with its famous pinned hinged trusses to allow movement.

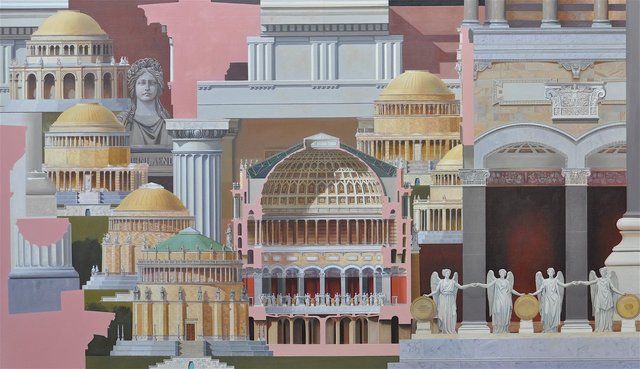

Befreiungshalle Mash-Up 8.7.16

This is my at least temporary title for the new painting. It seems appropriate as the word Befreiungshalle itself is a kind of “mash-up” of several words in that unique German language way of making compound words that has made my attempts to translate extracts from my books on von Klenze so difficult and time consuming. “Mash up” is what is becoming interesting and challenging about this painting. The translation from drawing to painting has revealed a number of things which do not work and others that are a challenge, requiring several changes in the composition to try and tie the different elements together a little more.

I am a little uncertain at this point about the pink areas where the buildings or elements are cut in section. This is a traditional technique that I have taken directly from the von Klenze working drawings I have found in the Bavarian State Library in Munich.

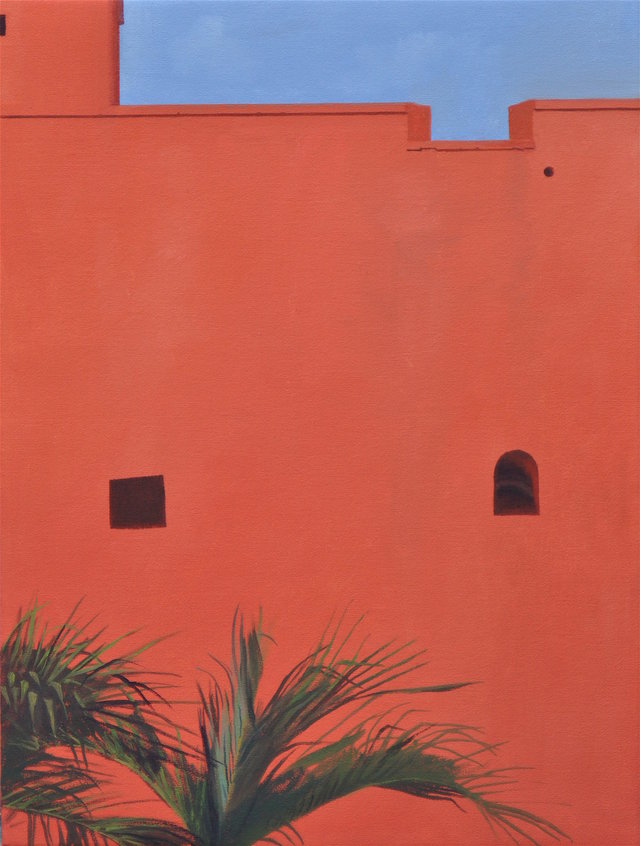

But I am wondering if it might also link that tradition to the Purist paintings and colours that appear in the Pessac paintings I have been working on recently. I think this might make a case for showing the two strands of work together. I am planning an exhibition at Plus One Gallery in November and wondered if there was a way to incorporate the Pessac paintings as well as the von Klenze work and perhaps also the red Danish fort on St. Thomas that I have just painted.

13.7.16

This painting is very hard to talk about as the changes and manipulations of the composition are so intuitive, much of the time I do not know where the painting is going. It is a bit like the idea of a sculpture being imprisoned in a block of stone and having to be released. I tend to have one good day followed by one despairing day as the painting progresses!

I no longer have doubts about the pink areas where the building is cut in section and the link to Purist paintings is becoming more noticeable. I think this painting will provide the link to the Pessac paintings I hoped it would.

Befreiungshalle 6.8.16

23.8.16

8.9.16

I have written an introduction to the November exhibition at Plus One Gallery:

A Sentimental Journey

“Journey” is a term I prefer to avoid in any context other than actually traveling from A to B as it is so overused (along with iconic). So I astonished myself when I settled on A Sentimental Journey as the title for this exhibition. I was reading Laurence Sterne’s satirical novel of that title about the 18th century Grand Tour, and it suddenly struck me that the title was very appropriate to my paintings of Leo von Klenze’s work in this exhibition, so steeped is his architecture in the study of antiquity from his journeys through France, Italy and Greece visiting many of the sites of the Grand Tour but studying them in a much more intense manner than that of a tourist. This journey was not just the mental or emotional journey of the clichéd term “journey” but actually did involve traveling to many of the major archaeological sites of antiquity and studying them through making sketches of the remains and drawing or painting reconstructions.

It should also be pointed out, as the introduction to my copy of Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey does, that at the time of its writing in the mid 18th century, “sentimental” had a quite different meaning to what it does now. It “did not have the pejorative sense of ‘excessively emotional” or ‘mawkish’ that it has since acquired.” The meaning was more to do with being in a mood of reflection and of being in sympathy with the object of reflection. This is certainly evident in the beautiful drawings and paintings von Klenze made of his travels.

I was given a book on von Klenze’s drawings and paintings by the architect Léon Krier back in 1987 when I was working on a painting of Krier’s Atlantis project. It was my introduction to this early nineteenth century Bavarian architect’s work. Von Klenze was a contemporary of Schinkel but is now less well known, hardly known at all in Britain. The book did not include much about his architecture but mainly focused on the drawings and paintings he made on his travels through Italy and Greece. I did not really appreciate the extent and beauty of his architecture until starting the research for these paintings.

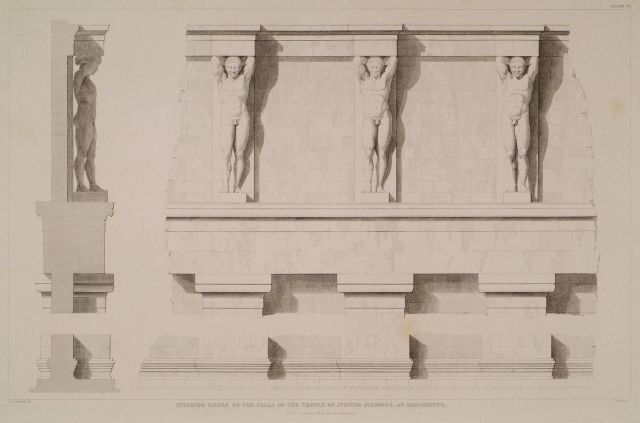

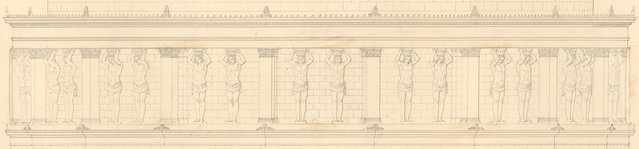

I have long admired the English architect C. R. Cockerell both for his architecture and his painting. He inspired my first architectural capricci with his paintings The Professor’s Dream and A Tribute to Sir Christopher Wren, which combine numerous buildings out of their contexts in imaginative compositions. I was interested to find that von Klenze was almost the exact contemporary of Cockerell and their careers have many similarities. They were both architects, painters, archaeologists and architectural theoreticians.They both received the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture from the Royal Institute of British Architects within four years of each other, so presumably von Klenze did have some following in Britain at one time. It is an interesting thought that von Klenze and Cockerell, as they formed their architectural styles, visited and drew many of the same archaeological remains in Greece and Italy. They shared a particular interest in the Temple of Olympian Zeus at Agrigento, both men having made measured drawings of the remains of the temple and drawings reconstructing the building and its Atlantes or giant columns in the shape of male figures. These feature in many of von Klenze’s designs including the Befreiungshalle and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg which can be seen in the paintings in this exhibition.

C.R. Cockerell

Leo von Klenze

Leo von Klenze, Befreiungshalle, Detail of Early Design

This study of antiquity on the Grand Tour links von Klenze to British architects like Cockerell , Sir John Soane, Stuart and Revett and many others from Europe and even the USA who shared at this time much common ground, across borders, in what was really an international style.

The second group of paintings in this exhibition concerns that other International Style that emerged in the 1920’s. These paintings are small studies of Le Corbusier’s 1925 housing for workers in Pessac, Cité Henri Fruges. This French housing project, similar to Britain’s Garden Cities projects, was to provide affordable housing for the workers in Henri Fruges’ sugar refinery.

There are also four variations on a painting depicting Léon Krier’s hypothetical project “revisioning” Cité Henri Fruges. This forms part of a larger Krier project to create a 9th volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre Complete subtitled: “Le Corbusier after Le Corbusier”; LC Translated, LC Completed, LC Corrected. Léon Krier appears to be a unifying thread running through this exhibition, having introduced me to the work of von Klenze and initiating these Pessac paintings.

To return to the title of this exhibition, A Sentimental Journey, sentimental is not a term generally associated with the architecture of Le Corbusier. However, I remember talking to Léon Krier at an RIBA exhibition, Three Classicists, in 2010. We were joined by someone who recounted having a well known modernist architect remark to him about the exhibition, “It would be fine if it were not sooo nostalgic”. I thought at the time that this architect’s own work was so permeated by Corbusian nostalgia that it could fill a whole new volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre Complete. I feel early Modernism has become an historical style with its own sentimental nostalgia and now, 91 years after the building of Cité Henri Fruges, one could take a sentimental journey back to early modernism and look at it in the same affectionate way one might look at the architecture and urbanism of Leo von Klenze. Both reward the study.