”The first five Driehaus recipients … are our teachers. One wishes their buildings, gardens and public spaces could be all gathered in one place to savour…” Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk addressing the Sixth Driehaus Prize audience.

The Driehaus Prize was set up ten years ago by Chicago businessman and philanthropist Richard H. Driehaus to honour “a living architect whose work embodies the principles of traditional and classical architecture and urbanism in contemporary society, and creates a positive, long-lasting cultural, environmental and artistic impact. It is presented annually by the University of Notre Dame.” The first ten recipients of the prize were Léon Krier, Demetri Porphyrios, Quinlan Terry, Allan Greenberg, Jaquelin T. Robertson, Andres Duany & Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, Rafael Manzano Martos, Robert A. M. Stern and Michael Graves.

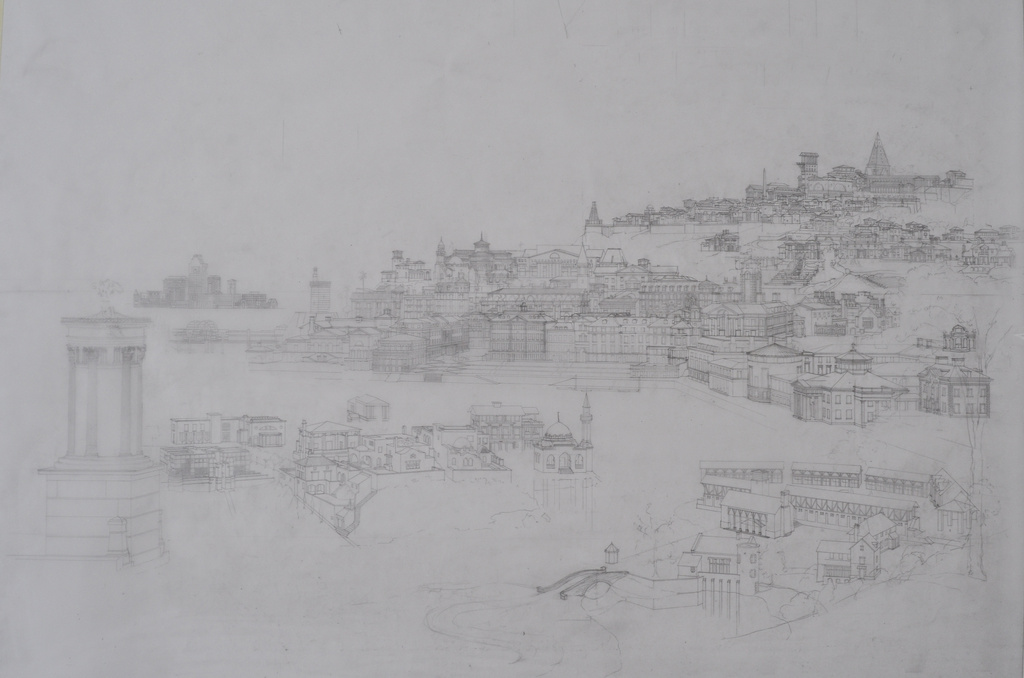

It was decided to mark the tenth anniversary of the prize by commissioning a capriccio depicting the work of the first ten recipients. I was asked to prepare sketches showing what such a capriccio might look like. I produced drawings, but more importantly, a small oil study that contains the basic elements of the composition.

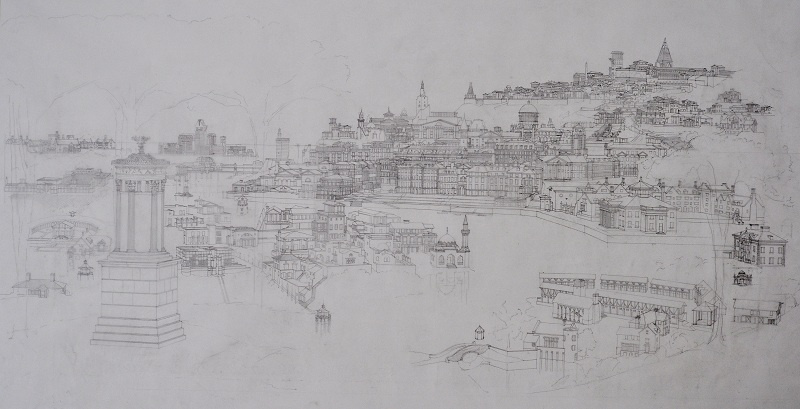

The proposed composition was accepted by Richard Driehaus and a year long project began, gathering information on the work of the ten architects and developing the sketches into a more detailed design.

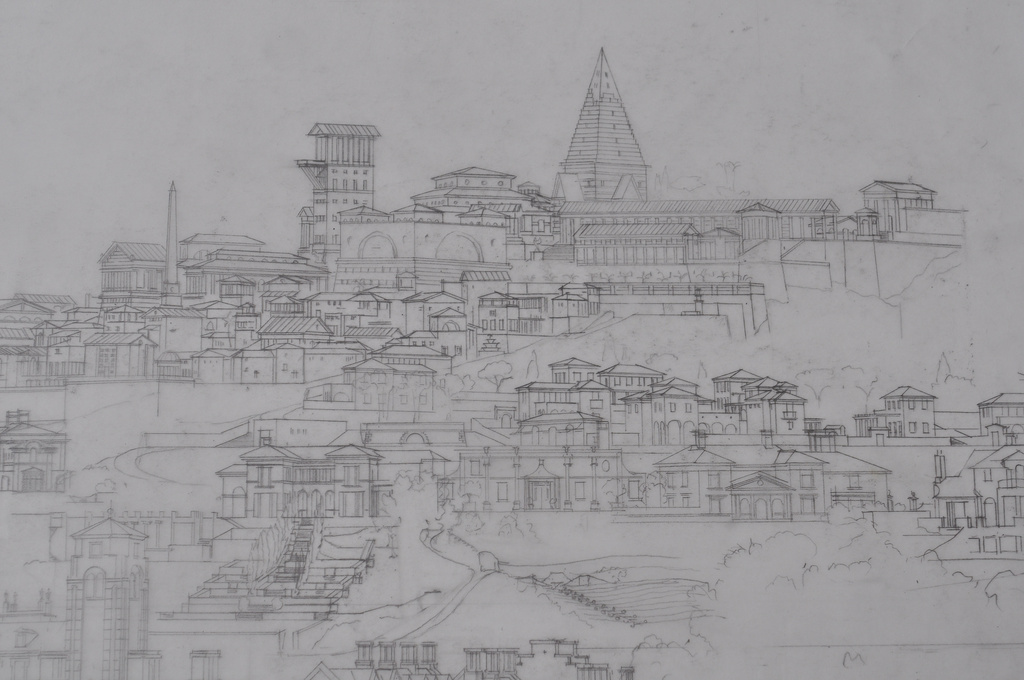

The painting is large, 165×250cm. Part of the work’s interest lies in the fact that all the buildings depicted are by living architects, apart from the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, in the foreground, and a number of restorations of older buildings by Rafael Manzano Martos, the 2010 recipient of the prize.

The Choragic Monument was included on the suggestion of Michael Lykoudis, Dean of Architecture at Notre Dame University. It is the symbol of the Driehhaus Prize and each recipient receives a bronze model of the Monument by Tim Richards. In the composition, the Monument is placed along the path that leads into the painting rather like a wayside shrine, appropriate as this and a number of similar monuments were placed along a street in Athens, the “Street of Tripods”. The image in the painting was reconstructed from photographs of the original taken by an Athenian friend and from James Stuart and Nicholas Revitt’s drawings in “The Antiquities of Athens”. The drawings were crucial as much of the original is eroded, missing or buried.

I also had an old photograph I had taken in the 80’s of Stuart’s reconstruction of the Monument at Shugborough which included his version of the tripod at the top, so I went to Shugborough to have a closer look, only to find the tripod had been stolen. I was left with my photograph as the only record of what the tripod “might” have looked like in Stuart’s hypothetical reconstruction. An 1892 article from the American Journal of Archaeology provided details of the frieze which is much eroded.

Apart from representing work by living architects, this painting is also unlike my capricci of Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor, Wren, Ledoux, Palladio, and Cockerell in that it combines the work of several architects rather than concentrating on one. Would it come together as a coherent whole when so many diverse approaches to classicism were put side by side? My intention was to make a unified landscape from the work of architects from Luxembourg, Greece, England, the USA, Egypt and Spain.

The composition is loosely based on the formula for a classical landscape painting as described to me by John Outram in 1987 when I was doing a painting for him, _Imago Terrarum. Basically, in his formula, one enters the picture from the countryside, across a bridge, over a stream which winds its way into the painting. One passes through the agrarian countryside to the town with its harbour and upwards through different levels of civilization before arriving at the Acropolis where the ideas reside.

In this case, we cross a bridge that is part of Demetri Porphyrios’s Belvedere Village which represents Outram’s agrarian aspect of the classical landscape.

We pass a mainly residential sub-urban area to our left with a further agrarian element in the form of Michael Graves’ Clos Pegase winery. The composition was reorganized and expanded to the left to accommodate this, and the area on the extreme right was also redesigned at this point, replacing a Porphyrios Oxford college design with his built Magdalen College project, and repositioning Quinlan Terry’s Corinthian Villa in Regents Park.

The main town lies at the centre of the composition, built around Quinlan Terryʼs Richmond Riverside and extended to form a harbour by the addition of Jacquelin Robertsonʼs Charleston County Courthouse and New Albany Country Club which are similar in character.

I have seen the Richmond Riverside development many times but decided to visit again to get a better idea of how the terraces that step down to the river were treated. This was just before the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and I had the good fortune to find the barge built for her river pageant moored on the quay. As this was to be an anniversary painting, I felt anchoring it in time to that other anniversary was appropriate.

Behind the harbour, in the densest part of the town, are the more highly urban buildings from Manzano Martos’ Sevilla, a church by Allan Greenberg and university buildings by Greenberg and Robert Stern with an appropriately urban character.

Continuing our journey up the hill, we eventually arrive at the “acropolis” from Outram’s formula, which in our case is Léon Krier’s utopian project, Atlantis. Just below it is Porphyrios’ town of Pitiousa, extending outward from Atlantis seamlessly and suggesting that perhaps the utopian is achievable. Below Pitiousa is an area occupied by a series of Robert Stern villas that sit comfortably between the Greek hill town and the larger town below.

The composition continued to develop and change on canvas over the next seven months; buildings coming and going and shifting minute distances. I also found the landscape changing in the painting as the seasons progressed in reality, reflecting what I would see on my walks in the countryside. I became determined to finish the painting before autumn which would require a major shift in the tonality of the work.

In the completed work, I think the diverse approaches to classical or traditional architecture do combine to create a harmonious composition through their shared principles with surprising resonances occurring in unexpected juxtapositions. I thought this was true of the Atlantis/Pitiousa/street of Robert Stern Villas sequence mentioned earlier. I found the middle ground peninsula with a slightly mediterranean flavour is another. Tropical residential buildings by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Jaquelin Robertson establish a Mediterranean influence that is continued in buildings by Léon Krier, Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, Michael Graves and Robert Stern. Here buildings from Florida, Jeddah, Egypt, Greece, the Dominican Republic and New Jersey sit comfortably side by side. I can also see ripples of influence that run through the centre of the main town. The Moorish influence that can be found in many of Manzano Martos’ restoration projects find sympathetic neighbors in El-Wakil’s Jeddah Lighthouse and mosques, and Duany Plater-Zyberk’s Alys Beach House at one end of Manzano Martos’ Calle San Fernando and Allan Greenberg’s Rice University Humanities building at the other end. Even Porphyrios’ Duncan Galleries in Nebraska does not seem out of place next to El-Wakil’s Corniche Mosque both constructed of lively, highly articulated forms that catch the light dramatically.

The book: Timeless Architecture: A Decade of the Richard H. Driehaus Prize at the University of Notre Dame by Richard H. Driehaus (Author) , Paul Goldberger (Foreword) is available from Amazon and contains the painting with a full key guide of the buildings within it.