Wine turns out to be a rich and significant part of my work as a painter and it begins in 1987 when Jean Dethier, architectural curator of exhibitions at the centre Pompidou in Paris, began to prepare an exhibition called Chateaux Bordeaux.

The birth of this exhibition is a story in itself. As I understand it, Jean Dethier received a phone call from a Jean-Paul Kauffmann, asking if he would be interested in mounting an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou about the Bordeaux Chateau as a unique building type, perhaps one of the first building types invented primarily as a marketing exercise, rather than a chateau as a residence, designed to impress and sell wine, especially to the British. Dethier was interested in the idea and they agreed to discuss it further when Kauffman returned, as he was calling from the airport, about to catch a flight to the Lebanon in his capacity as one of two Directors of the magazine L’Amateur de Bordeaux. The other Director, Michel Guillard, worked closely with Dethier to realise the exhibition over the next three years as Jean-Paul Kauffman was kidnapped in Lebanon and held in captivity for those three years, only being released a fortnight before the exhibition opened. It was my great honour to be asked by him to sit at his table at the opening dinner as one of the paintings I produced for Chateaux Bordeaux, Un Reve d’Architecte dans le Médoc, seemed to him a representation of the idea that had kept him sane during three years of solitary captivity: the list of the 61 chateaux that make up the Grands Crus Classés en 1855 – the very best wines of the Médoc. My painting was a partial (partial as time was short) representation of those chateaux that I would go on to represent in a complete version at a later date. Jean-Paul Kauffman related that he kept his sanity by trying to recall the 61 chateaux – in order. When he had mastered that he tried to recall the taste of the wine from each.

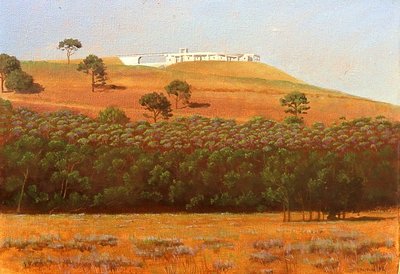

Returning to the gestation of the exhibition, it was conceived to be in three parts: an historical survey of the development of the chateaux, an ideas competition inviting several architects to submit their ideas for a new chateau, and an actual competition for a new chai at Chateau Pichon-Longueville, which would be built. Jeremy Dixon, who I had worked with for several years on the Royal Opera House among other projects, was asked to submit a design for an imaginary new chateau. He insisted on having an actual site, arguing that to build a chateau without context was nonsense. A very sound argument bearing in mind the importance of the site, terroir, to wine making. A site in the property of Duhart-Milon, managed by Chateau Lafite, was selected as Duhart-Milon has no actual building. Jeremy produced a design which he asked me to do a painting of:

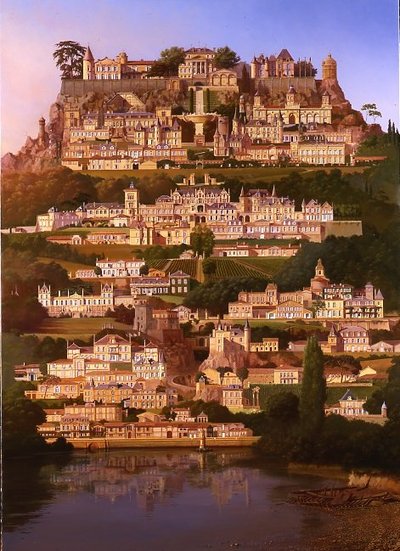

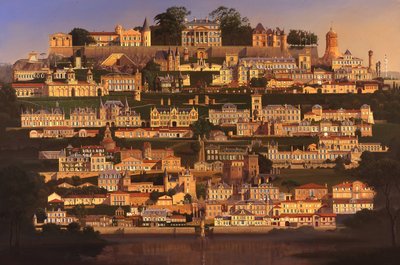

On seeing this, Dethier asked if I would do a painting of Dillon/de Gastines’ winning project for a new chai at Pichon-Longueville. I felt this would reduce the impact of Jeremy’s presentation and declined. Dethier then asked if I might paint an overview of the exhibition – a painting that brought together the various elements that were to be displayed. I felt there would not be any confusion between this and Jeremy’s presentation and accepted. I began a painting, Un Reve d’Architecte a Bordeaux, which combined the type of elements that were going into Dethier’s exhibition in an interior taken from Chateau de l’Hospital in Bordeaux, one of the interiors I found particularly beautiful and moving in my visits to the various chateaux with Jean. I had to put this aside, however, as Dethier had arranged the patronage of Bruno Prats of Chateau Cos d’Estournel and at that time the Chairman of the Syndicate des Grands Crus Classés du Médoc for a painting depicting as many of the 61 chateaux that make up the classification as possible in the time.

This arranged the chateaux on five levels corresponding to the five crus which ranked the chateaux in the 1855 classification which is still used.

This was used in the Paris exhibition at the Pompidou and I went back to the first idea and finished that painting so that it caught up with the exhibition when it moved to Bordeaux.

I was then commissioned by the Syndicat des Grands Crus Classés to do a complete version of the 61 chateaux of the classification and had a wonderful time visiting each chateau.

Marvin Shanken of The Wine Spectator commissioned a version for their offices in New York, with the approval of the Syndicat, which I put into a different format.

And Bruno and Jean-Marie Pratts commissioned a painting depicting the seasons and the stages of wine making at Cos d’Estournel. This involved visits at several seasons and a particularly memorable trip with my then young son Max during the vendange. We had Chateaux Marbuzet, Cos’s second chateau, all to ourselves – with a cook! Max took part in the vendange with the army of Spanish pickers whom we had our lunches with daily. Evidently Cos was a top choice for the harvesters as the food was so good.

I did a few other paintings of the Médoc at this time of scenes which caught my eye.

The connection with the architects Dillon/de Gastines led to paintings for them in 1990 of the new chai they built for Michel and Christine Guérard at their Chateau de Bachen near their spa, Les Prés d’Eugénie at Eugénie les Bains in the Landes region. The memories – gastronomic and sensual from this trip defy description. I know I arrived for the first time in the dead of night with Patrick Dillon to see the site for the first time. Michel Guérard had left out for us a late supper of carpaccio of duck accompanied by a bottle of Chateau Dillon – no relation to Patrick, but a thoughtful choice. To remember a meal after 25 years is a tribute to the chef, not my memory! When I woke up the next morning and looked out on a mist shrouded rural landscape, complete with Monet like haystacks built around poles, there was a slightly pungent but pleasant smell in the air from the sulphur of the bains. I remember indulging in magnificent lunches as guests padded past the dining room in white bathrobes on their way to their various “treatments” such as coatings in porcelain clay!

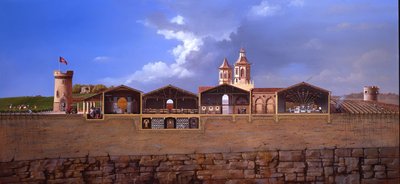

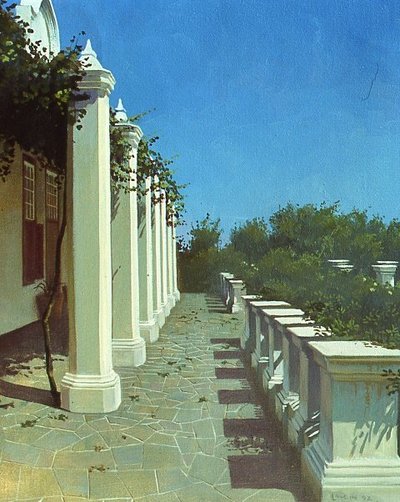

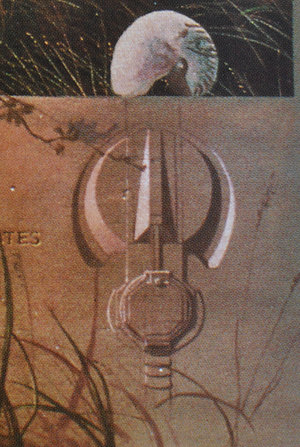

The original approach to me to paint Dillon/de Gastine’s winning design for the new chai at Pichon-Longueville resurfaced in 1991 after it had been built. Study for a Mural in Azulejos at Pichon Longueville, 63×84cm, oil on canvas, 1991, is a fragment of a design for a series of murals in the new chai at Chateau Pichon-Longueville. Murals were to be located at either end of the new barrel room which was to be mainly dark, with only decorative column capitals and the murals lit. One end of the barrel room has a viewing gallery where the mural was to be seen close up and that was to have an explanation of the development of the design for the chai, of which this is a fragment, showing influences on and stages of the design.

The other mural, seen from a distance down two “Avenues” between the dark rows of barrels, was to have a scene of the actual Gironde at the end of one “Avenue” and an arcadian fantasy of the Gironde at the end of the other. They were to be rendered in glazed Portuguese tiles, azulejos, so that they would be resistant to the atmosphere in the new chai. Sulphur is used to sterilise barrels in the chai and it was felt that this could have a detrimental effect on traditional oil paint.

The murals were never realised, but the research into the technique of azulejos on visits to Lisbon and Sintra was not to be missed. It was in the course of this research and when the Chateaux Bordeaux exhibition travelled to Oporto that I was introduced to the Douro region for the first time. The architecture of the terraced port vineyards was staggeringly beautiful and I remember one of our hosts on that trip, Joao Nicolau de Almeida of the port house Ramos-Pinto, describing them as “our pyramids”. We were treated by him to a wonderful lunch on a vine covered loggia overlooking the terraced vineyards and were told that everything on the table came from the farm – except the fish – which came from the Douro! Honestly, I would have been happy with just the tomatoes, they were so ripe and full of flavour. Joao set me a challenge which I have never managed to meet – to paint the taste of wine. The closest I came was in South Africa, where I felt the paintings did manage to evoke, for me at least, the powerful aroma of the fragrant grasses and thatched roofs. Joao finished the lunch with an ancient bottle of tawny port made by his grandfather. Jean Dethier, who was leading this visit to the Douro, was eager to catch the last train down the Douro Valley to Oporto and we had hardly touched this port, so Joao dashed into the house and returned with an empty Coke bottle into which he decanted the port, stopped it with a cork, and presented it to me with the instructions that it had to be consumed within 24 hours. Happily he appeared at our hotel the next day and helped with that task. The train journey, made in the driver’s cab Dethier managed to talk us into was stunning.

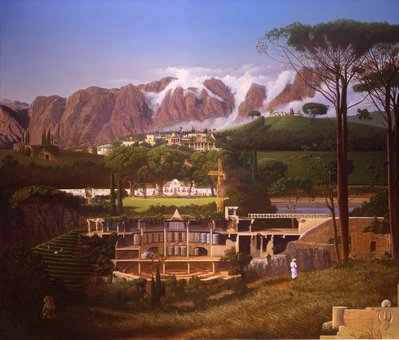

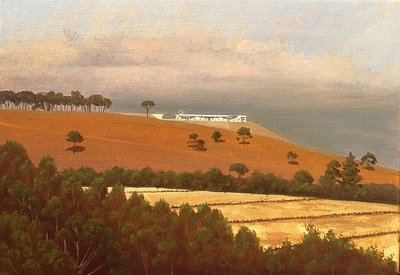

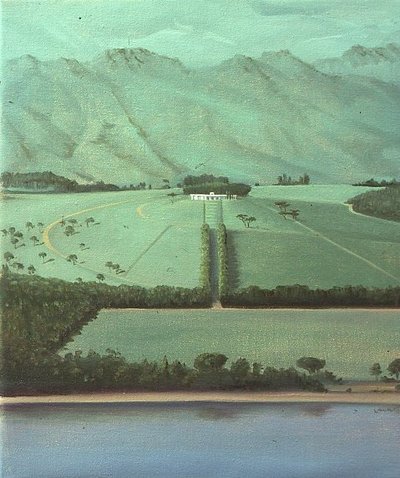

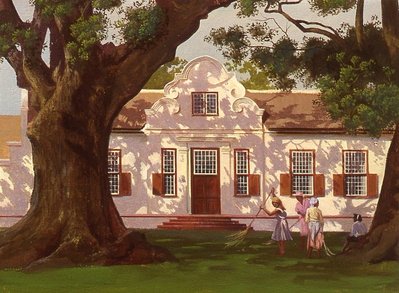

The connection with Dillon/de Gastines led in 1992 to a series of paintings for Anglo-American Farms of the new winery they were building at Vergelegan. This was in the grounds of the house Willem Adriaan van der Stel an early governor of the Cape Colony built outside Capetown. The winery is set on a small hill which acts as the hub of the great wheel of the Hottentots Holland mountains. Because of the beauty of the site and the mechanics of wine making (making the most of gravity movement of the maturing wine and the insulating properties of the ground) the majority of the winery is set below ground into the hill, Rondekop, I think it is called.

Van der Stel was impeached for overstepping his authority by building himself a grand estate at Vergelegan. The document condemning him included a drawing of the Vergelegen estate as a grand symmetrical composition extending with formal axes into the landscape. Van der Stel responded to this with a similar drawing which showed Vegelegen as a modest house surrounded by great mountains, wild ferocious animals and spear brandishing natives. Nick Diemont, who was in charge of the work at Vergelegen, suggested that I should produce two paintings that reflected these two documents in some way, which would hang either side of a window in the the visitors’ tasting room in the new building, overlooking the vast internal space of the winery.

I eventually decided that the new winery building reflected nicely the difference between the two historical drawings. Both drawings essentially show the same building but put emphasis on different aspects of it to good effect. The first drawing, very formal and stylized, emphasizes the grandeur of van der Stel’s creation, verticals are stressed to add importance and you enter the picture by moving up it, not into it, accentuating the idea of a grand architectural progression. Van der Stel’s drawing emphasizes the breadth of the landscape, diminishing the importance of the house and making it appear all too small for its setting. The new winery parallels this idea of two very different images of the same building by burying the bulk of the building in the ground so that a grand, formal, symmetrical structure, incidentally organized vertically to suit the mechanics of wine making, appears externally as a very modest horizontal line in the landscape. The two paintings reflect this dual interpretation of the same object, one showing the building as a modest, minimal intrusion in the landscape and the other revealing the actual extent of the building, its grand internal space and the formality of its geometry.

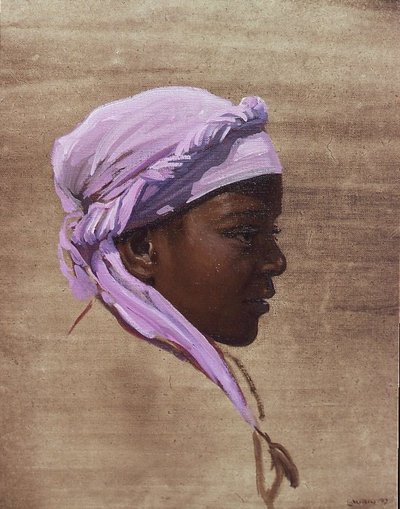

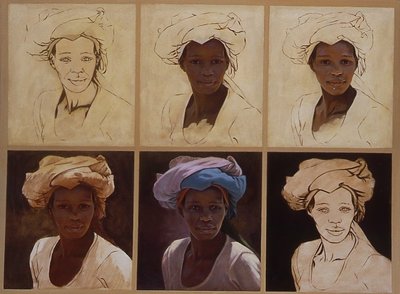

Inspired by the beauty of the landscape, I produced a series of smaller works depicting the winery from different angles, views of the house and garden and several paintings of the women working in the vineyards which I made copies of for the individual women. One of these paintings, of Sandra Mqena, I liked so much at different stages, I found it difficult to decide if I should carry on to the next stage or leave it unfinished, so I decided to do a multiple portrait of her at different stages of completion.

The paintings were exhibited at Sotheby’s Johannesburg and at Vergelegen. Some of the paintings were also adapted to be used as labels for the wine and a small detail in the painting of the building in section showed the plan of the new winery as a fossilized crustacean along with a chambered nautilus which the architects had in their atelier whose form seemed to fascinate them. This crustacean has become the symbol of the winery, used on labels and capsules.

Here is one last view of the winery; a view which I wanted to do and began, but never finished until this year.