When I first saw Castle Howard, in the autumn of 1973, it was not open to the public that day and we could not visit, but we looked across the mists of the lake at its astonishing profile. I had no idea then that I would become a full time painter, let alone be so involved in painting that house and be so generously supported by its owner. It was over twenty years later after I had made the transition from architect to painter that I contacted The Hon. Simon Howard about visiting Castle Howard in conjunction with a painting I was planning on the work of Nicholas Hawksmoor.

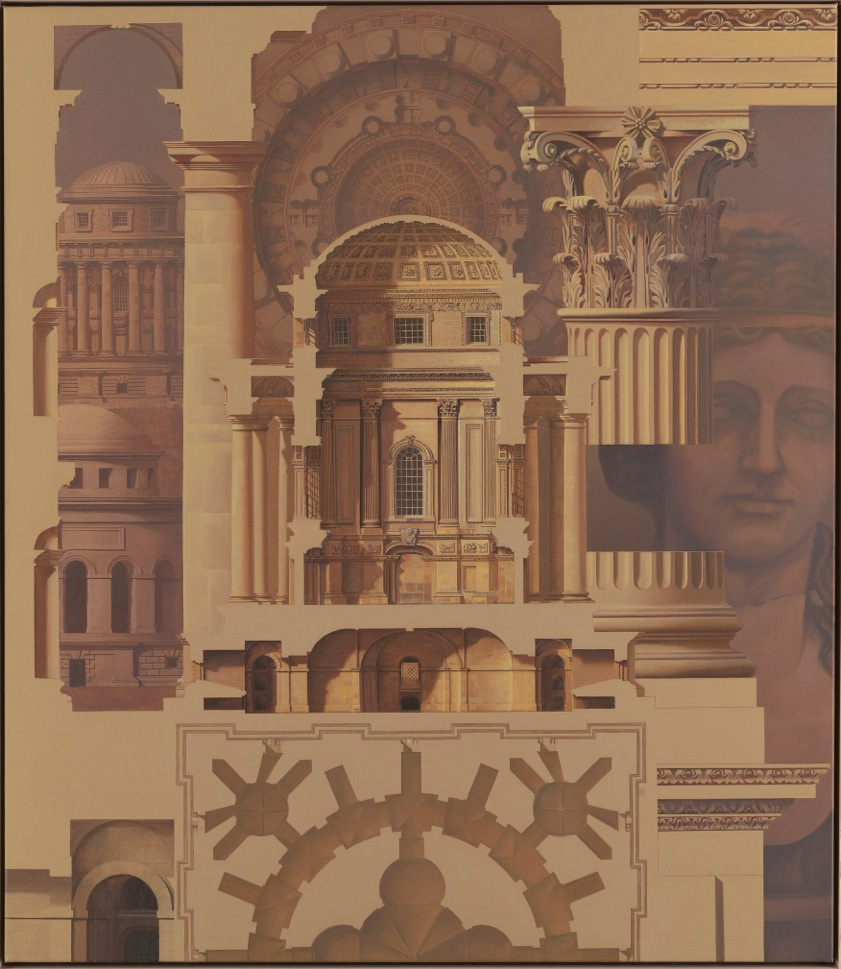

Hawksmoor,102cmx203cm,oil on canvas, 1996-2000

I needed information on Hawksmoor’s Mausoleum at Castle Howard to construct a section of the building in the foreground of the painting. Simon Howard’s reply was immediate, inviting Christine and I to Castle Howard and taking us on an enthusiastic tour of the estate, not only to every main, well known feature of the park but also introducing several monuments also by Hawksmoor hidden in the woods, well off the beaten path, which would find their way into the painting. During this visit to collect information for the Hawksmoor painting, I was commissioned to do a capriccio of the Castle Howard buildings. The resulting composition was only reached through lengthy correspondence, Simon Howard playing an equal part in developing the ideas behind the painting and selecting the elements to be included.

Castle Howard Capriccio, 122cm x 183cm, oil on canvas, 1996

This capriccio was accompanied by a number of paintings of individual buildings which was to become a typical way of working for me.

Pyramid, Castle Howard, 30cm x61cm, oil on canvas,1997

Temple of The Four Winds, 71cmx71cm, oil on canvas, 1997

Temple of The Four Winds, 71cm x71cm, oil on canvas, 1997

The Atlas Fountain, Castle Howard, 30cm x 25cm, oil on board, 1996

Temple of the Four Winds,122cmx96cm, oil on canvas, 1997

A second commission from Castle Howard came later, commemorating the restoration of the Monument to the VIIth Earl of Carlisle as part of their ongoing programme of restoration work. The Monument had been erected by public subscription and reflects the esteem in which the VIIth Earl was held. The inscription on the pedestal reads,

“HE TO WHOM THIS MONUMENT WAS RAISED AD MDCCCLXIX IN PRIVATE LIFE WAS LOVED BY ALL WHO KNEW HIM BY HIS PUBLIC CONDUCT WON the RESPECT of his COUNTRY and LEFT THE BRIGHT EXAMPLE OF A TRVE PATRIOT AND EARNEST CHRISTIAN.”

The tripod at the top of the monument was being replaced, having been struck by lightening, and the whole of the monument was being cleaned. As the monument was scaffolded out for this, it was a wonderful, if terrifying, opportunity to see all the high level detail at close quarters, undistorted by a ground level viewpoint, and it presented the possibility of celebrating the beauty of the carving of the capital in great detail in the painting.

photos of the Monument taken before, during, and after restoration, giving some sense of the scale of the structure:

Monument to the VIIth Earl of Carlisle,153×122cm, oil on canvas, 2003

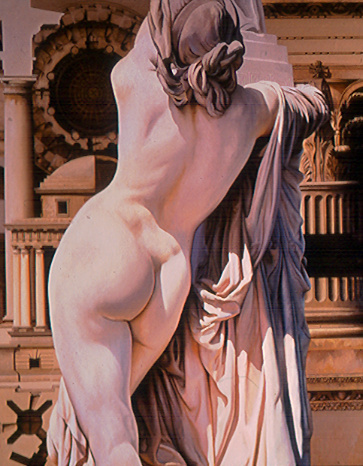

This idea of a capriccio built around a single building or object, and showing different aspects of it, led to two capricci depicting aspects of Hawksmoor’s Mausoleum. One of them was rather whimsically combined with a sculpture of Cassandra from the Tuilleries; some tenuous connection between the prophet of doom and the Mausoleum being an excuse to combine the geometrical sharpness of the Mausoleum with the softness of the human form. This experiment with sculpture led to a series of paintings depicting the human form through paintings of sculpture.

Mausoleum, Castle Howard, 117×102cm, oil on canvas, 2005

Cassandra and the Mausoleum, 122×122cm, oil on canvas, 2002

Again, restoration work and internal scaffolding in the Mausoleum gave me the opportunity to see the high level details at close hand and on another earlier visit I was allowed access to the roof of the Mausoleum and able to confirm my suspicions that the dome was actually shallower than the semicircular dome depicted in Charles Heathcote Tatham’s 19th century drawings of the Mausoleum which I had been given as a reference. This was not at all noticeable from ground level as the trompe l’oeil coffering gives the illusion of a hemispherical dome but from the ledge just below the springing point of the dome (unguarded by a railing and really testing my head for heights) one could tell it was a flatter dome than Tatham had shown. Constructing the section for the Hawksmoor painting suggested something was amiss between what one saw of the dome in profile on the outside, where it sprang from on the inside, and Tatham’s drawing. Tatham obviously had not ventured out onto that high level ledge. I can hardly blame him. But this information allowed me to complete the Hawksmoor painting which had remained unfinished for some four years.

Castle Howard eventually acquired the two paintings of the Mausoleum as well as a painting of the 9/11 disaster with its eleven accompanying studies. These 9/11 paintings were later exhibited at the house in a special exhibition in 2007. The Honourable Simon Howard and Dr. Christopher Ridgway, Curator at Castle Howard, wrote the following introduction to the exhibition:

Carl Laubin and the Painting of Elegos

Born in New York in 1947, Carl Laubin settled in England in 1973. He was so profoundly moved by the attack on the World Trade Centre on September 11th 2001 that as soon as flights resumed to the USA he returned to his birthplace in order to record the scene of the tragedy.

Carl Laubin is renowned for his ingenious and imaginative paintings of classical and contemporary architecture, so it is no surprise that his haunting testimony to the terrible events of 9/11 should focus on the fragments of the Twin Towers.

Although Ground Zero was a restricted zone, on the first day he was able to get near to the site where he began making sketches, and taking photographs, which captured the atmosphere, especially the smoke, dust, and haze. In the following days he was repeatedly denied access to the ruins (which were both dangerous and technically still a crime-scene) but he was able to walk around the perimeter of the zone and gain glimpses of the devastation from different angles. For him the most important thing was to be present at the scene itself, in his home city, to sense the scale of the event, and to absorb a world of devastation unlike anything he had ever seen before.

After four days Carl returned to England where he began to transfer these vivid impressions onto canvas in a series of oil sketches. These helped keep the images of Ground Zero alive in his mind’s eye, and enabled him to build towards the central work, initially through a series of drawings before the final composition in oil. Elegos itself is an amalgamation of several viewpoints, condensed into a single vision that tries to convey this sense of witness, of being surrounded by an immense destructive chaos.

Carl was particularly concerned that the powerful immediacy of what he saw in the aftermath was not lost during the protracted process of painting. His sketches and snapshots assisted him, as did his memories of sights, sounds, and smells. It is a deeply personal painting, it is not a documentary record like a photograph; and his title, Elegos, from the Greek word meaning elegy or lament, is his way of remembering those who lost their lives in the destructive events of 9/11. Thus there is a moving and reflective quality to these pictures, with the viewer invited to contemplate an enormous human tragedy amongst the wreckage of the skyscrapers.

ELEGOS,183×152cm,oil on canvas,2001

Simon Howard’s continued patronage also resulted in the purchase of The Queen’s Canova, a development of the interest in sculpture begun with Cassandra and the Mausoleum, and most recently Vanbrugh Fields, one of two capricci depicting the architecture of Sir John Vanbrugh, architect with Nicholas Hawksmoor of Castle Howard.

The Queens Canova,122cm x122cm, oil on canvas, 2003

Vanbrugh Fields, 122×198 cm, oil on canvas, 2011

With the two Vanbrugh capricci I made in 2011, I was able to look at some of the structures in the grounds like the bastion walls that had escaped my notice before. They are examples of Vanbrugh really indulging his romantic imagination and his fascination with medieval fortified buildings.

From the Last Bastion to Hawksmoor’s Pyramid, 71×107cm, oil on canvas, 2011

Bastion and Cypress Castle Howard, 25×30cm, oil on canvas, 2011

Round Bastion, Castle Howard, 35×25cm, oil on canvas, 2011

The Last Bastion, 107×71cm, oil on canvas, 2011

One of the astonishing aspects of Castle Howard is that visits always reveal something new no matter how many times one has been there, as the never ending restoration work will have brought changes and new elements are also being introduced. Perhaps much of the allure of Castle Howard is due to the landscape which Dr. Christopher Ridgway, Curator at Castle Howard has described as a capriccio in itself – a built capriccio – in much the same way Hadrian’s Villa is. These bastions at Castle Howard raise interesting questions related to capricci and garden follies, often built as ruins. When they fall into disrepair should they be restored? Or in their disrepair are they even more evocative of the classical arcadian landscape that became so popular an inspiration for English garden designers. On my next visit to Castle Howard the bastions had been restored. Vanbrugh had not built them as ruins but complete. Perhaps it was not Vanbrugh’s generation that saw these fanciful buildings in the landscape as ruins and perhaps his vision wanted them complete to allow the imagination to vividly recreate another era rather than muse on its passing.

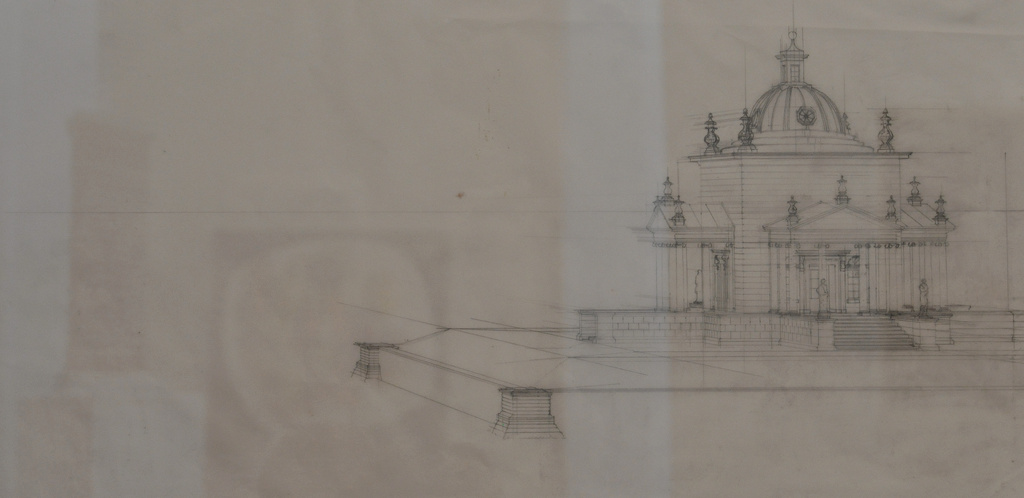

Perspective drawing of Temple of the Four Winds, 38×77cm, pencil on tracing paper, 2011

Farewell to Castle Howard, 60×50cm, oil on canvas, 2011

T4W, 60×50cm, oil on canvas, 2011

It is always a thrill to be allowed to roam around a piece of great architecture, discovering its hidden workings and secrets, but to have had the run of Castle Howard and to be so consistently supported and encouraged over the years in the way I have been at Castle Howard is to me an unbelievable honour that I never expected in a million years.